A pandemic lifetime ago (aka early 2020), when COVID-19 was still known as the novel coronavirus, the BCCDC’s Public Health Laboratory (PHL) was already performing genomic sequencing on early samples of the SARS-CoV-2 virus taken from patients in B.C. Their work has played a crucial role in tracking the spread of COVID-19 and responding to outbreaks. As the pandemic developed, so did the need to track and understand the virus.

“Why did we start sequencing this virus?” says Dr. Natalie Prystajecky, head of the Environmental Microbiology program at the PHL. “The answer is that in the beginning, we sequenced because we could. But as the pandemic progressed, sequencing has provided us with an in-depth understanding of what we are up against from the characterization of outbreaks, to the emergence of new strains, to understanding the interactions between the vaccines and the host response. Genomic sequencing allows us to understand the virus in as close to real time as possible.”

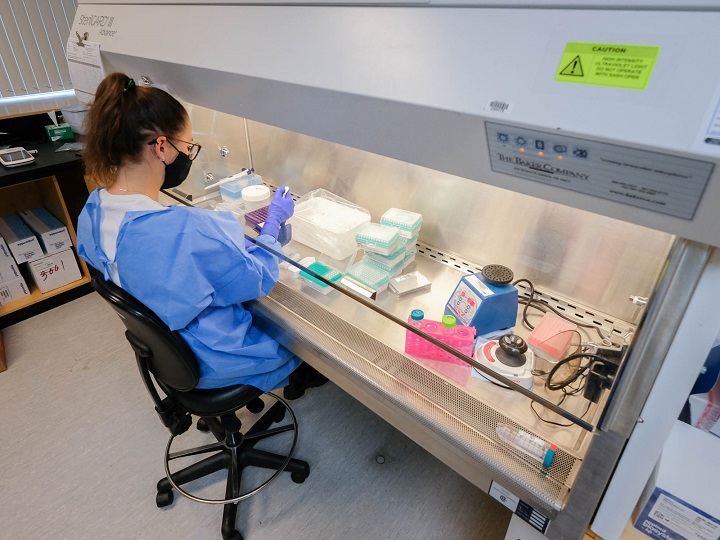

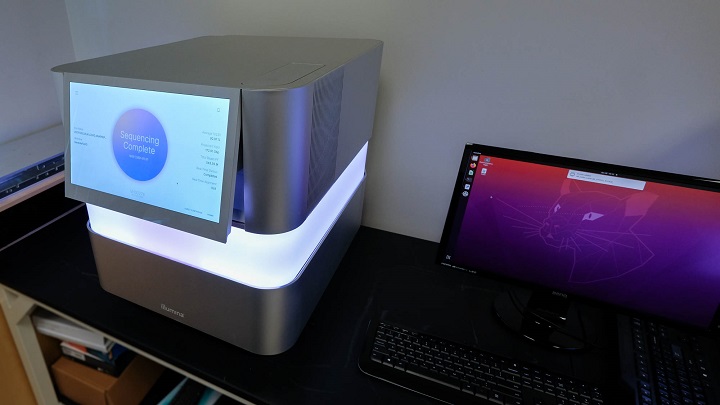

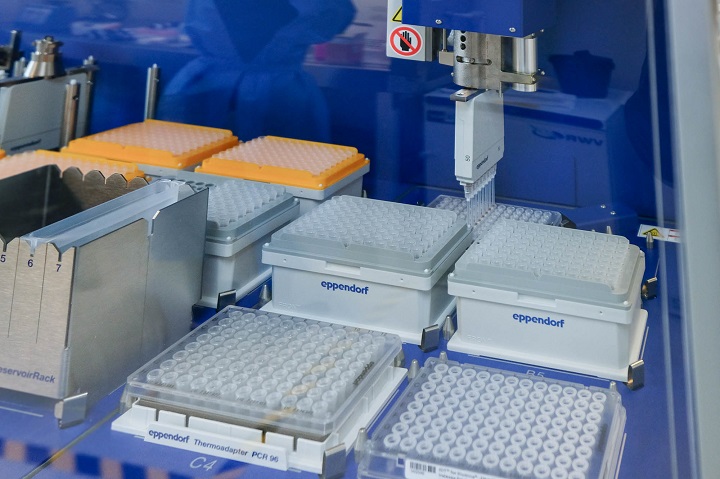

The teams of medical, scientific, technical and operational personnel working at the PHL have been sequencing a representative proportion of COVID-19 positive samples since the beginning of the pandemic. As the number of cases of COVID-19 grew in B.C., the PHL teams worked to build genomic sequencing from a shoe-string patchwork resource into a high-capacity and standardized operation. The PHL went from being able to sequence 24-48 samples in a week to being able to sequence over 2,000.

These efforts were co-led by Dr. Prystajecky and Dr. Linda Hoang, associate director and program head of the Bacteriology & Mycology Lab at BCCDC, along with the operational staff in the Public Health Advanced Bacteriology & Mycology Lab and the Molecular Microbiology and Genomics Programs. Their work was made possible by the contributions of many people at the BCCDC, including Dr. Karen Mooder, who supported the operational investment that allowed for an end to-end solution for sequencing, from the automation required to prepare the samples to the computational tools for analysis. Genomics specialists, such as Dan Fornika, were key in automating the analysis to support the sequencing. Dr. John Tyson, who recently came on board, and has been integral in keeping a sharp eye on emerging strains and reporting them as signals arise. There are also a number of technical and scientific staff members who work together every day at the BCCDC to make COVID-19 sequencing possible and generate data that informs the public health response.

It’s been more than a year since the first sample of COVID-19 was sequenced in January 2020, and the whole genomic sequencing done at the BCCDC has informed public health every step of the way. This leading-edge science has helped officials make key decisions and been used in over 350 cluster investigations. Genomic sequencing is now being used to investigate possible COVID-19 re-infections, track variants of concern and to monitor vaccine effectiveness.

In late 2020, word spread of new COVID-19 variants, known as variants of concern. BCCDC staff quickly realized these could change the course of the pandemic in B.C. The dedicated staff at the PHL got to work, looking for these variants in B.C. samples.

The B.1.1.7 variant, sometimes called the UK variant, is about fifty per cent more transmissible than other forms of the virus, while the B.1.351 variant that originated in South Africa and the P.1 variant that originated in Brazil may be more resistant to current vaccines.

When these new variants were identified, the dedicated staff at the PHL began searching for them in B.C., identifying the first case of B.1.1.7 on December 26, 2020.

“We all worked through the holidays to confirm this case and then we quickly pivoted to a strategy where we have an aggressive approach to identifying and sequencing variants of concern,” says Dr. Hoang.

The PHL’s COVID-19 genomics strategy acts like the proverbial canary in a coal mine, serving as an early warning signal that informs the laboratory and public health response. The increase in cases of the P.1 and B.1.1.7 variants in B.C. led to a change in the laboratory testing strategy to more rapidly identify and target outbreaks associated with variants of concern. Genomic sequencing work has also allowed officials to monitor how the virus is transmitting in B.C., and informed decisions around restrictions and other public health measures.

“This comprehensive approach to genomic sequencing makes B.C. a true stand out in Canada,” says Dr. Mel Krajden, the Medical Director of the PHL. “As of May 2021, B.C. had done whole genome sequencing on about 20 per cent of all COVID-19 samples, over 24,000 samples in total. This is far more than any other Canadian province and its real value is about enabling us to understand how well protected vaccinated British Columbians will be from emerging variants.”

“We were the first province to ramp up genomics sequencing capacity for SARS-CoV-2 and we continue to sequence a larger proportion of our samples than any other province,” says Dr. Prystajecky. “B.C. is really a leader in genomics on a national scale.”

The PHL is currently increasing their genomic sequencing capacity with the aim of sequencing 30 per cent of all COVID-19 samples in B.C. in the next few weeks. This is well above the federally set target of sequencing five per cent of all samples.

As people across the province head to vaccination clinics, PHL teams are working on sequencing vaccine breakthrough cases (instances where a person who has been vaccinated contracts COVID-19) to potentially detect vaccine-resistant strains and understand their impacts on vaccine roll-out.

Genomic sequencing is also used to investigate possible cases of COVID-19 reinfection, and can help determine if a person has indeed contracted COVID-19 twice, which is possible but rare, or if they’ve only been infected once but are experiencing chronic symptoms. This has implications for the patient’s clinical care and is also important for doctors and scientists tracking the rates of so-called “long COVID,” when patients continue to experience symptoms for months after their initial infection.

Such a robust program is made possible by the hard work of a large proportion of dedicated PHL staff, while still maintaining the routine public health and patient care diagnostic work in the background.

“We couldn’t have accomplished so much and become a national leader without such a dedicated and hardworking team,” Dr. Hoang says.